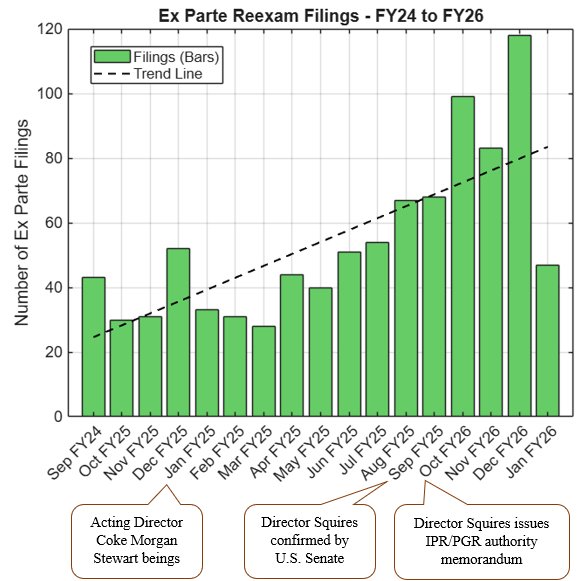

On February 6, 2026, the USPTO updated its guidance on anonymous requests for ex parte reexamination. When a patent has previously been the subject of an IPR or PGR that produced a final written decision on at least one claim, an anonymous requester must now include an affirmative statement that the real party in interest is neither the prior petitioner nor a privy of that petitioner.

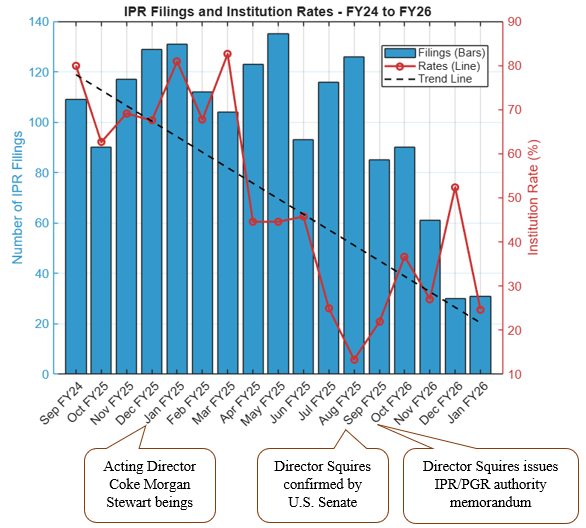

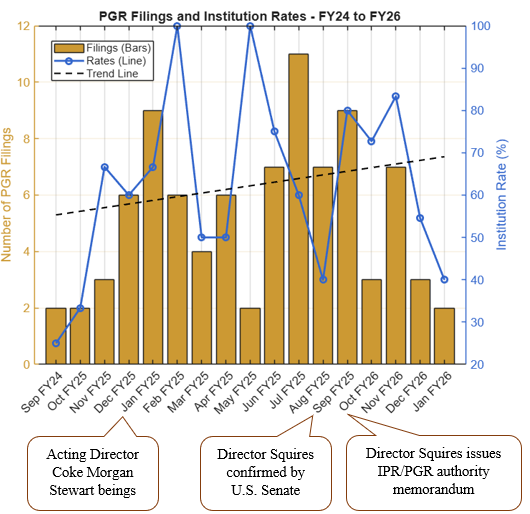

The change comes on the heels of the surge in ex parte reexamination filings we have seen since the USPTO began expanding discretionary denial authority in IPRs, as discussed here. The updated certification requirement is a direct response to instances where challengers may have sought a second (or third) bite at the apple through anonymous reexams.

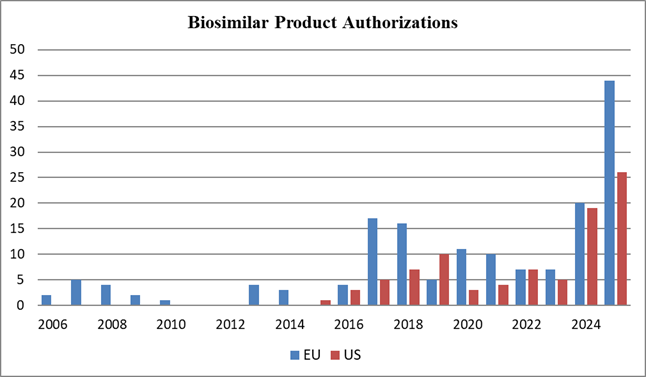

For pharmaceutical patent owners, this is a welcome response to the rise in ex parte reexamination filings. Serial challenges, even in different forums, increase litigation risk and uncertainty during the critical pre-launch window. For potential challengers (including biosimilar applicants including collaborators and companies existing in parent-subsidiary or licensor-licensee situations), the updated certification requires careful vetting of real-party-in-interest relationships and will likely discourage some parallel-track strategies.

The message is clear: the post-reform PTAB environment continues to evolve, and sophisticated parties must plan their validity challenges holistically across district court, IPR, PGR, and reexamination avenues.